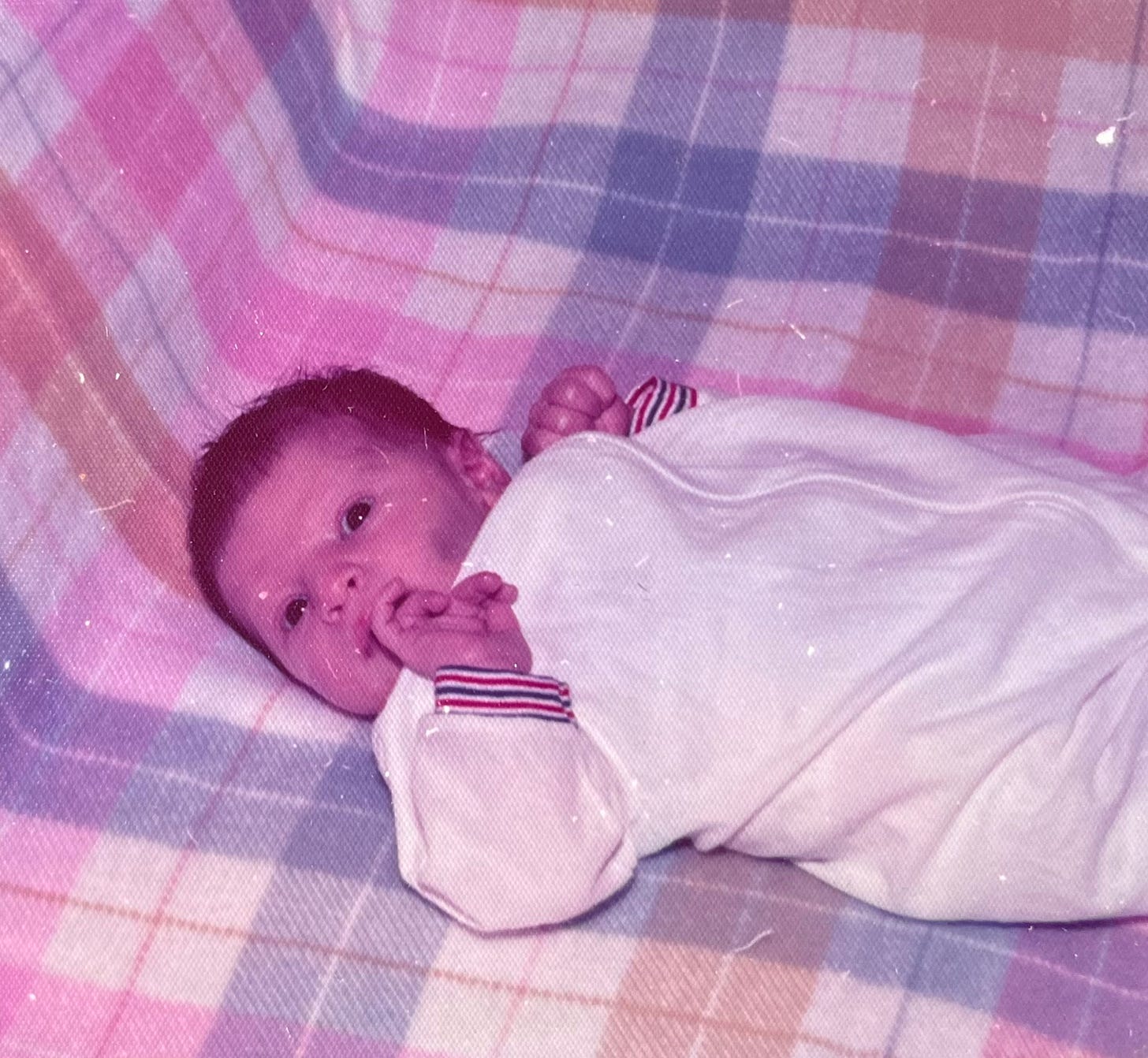

One of the really impactful cases that I worked as a crisis responder and have mentioned in a few interviews over the years was the one I refer to as “Basketball Baby”.

I got the call to transport a young child from the Children’s Hospital’s Emergency Department to an emergency foster placement late one night. I was told that the nurses would fill me in on the details once I checked in.

I arrived at the desk to see one nurse cradling the child, who was probably under 10-months old, with another nurse on either side of her fawning over him.

Another nurse stepped away to get the paperwork for me, while the one holding him placed him into my arms.

He was heavy—like a sack of potatoes. Limp. Motionless. Just dead weight on my crossed arms.

His bright, round eyes locked onto mine, unblinking. His deep, dark skin was flawless, his face eerily still—perfectly symmetrical, yet absent of expression. Long, rhythmic breaths visibly filling his little lungs.

One of the nurses wiped back tears as she asked where he was going. I told her to a foster home about an hour away.

The paperwork arrived and I was briefed on the story as the little boy laid still in my arms, never flinching.

Apparently he came to the hospital after being removed from a domestic violence situation, where the father would throw him against the wall to torment the mother.

Due to the melanin in his skin, no bruising was visible—though nearly every bone in his little body was broken.

That hit me hard.

I held him close to my chest until I had to strap him into the car seat—an incredible feat as he couldn’t move any of his limbs himself and I was terrified of causing him any pain.

Luckily they’d given him plenty of painkillers to take the edge off, as no casting or bandages could be used at that stage of development.

He didn’t seem bothered by anything I did, taking great care to be especially gentle with the transition—never taking his eyes off of mine as if to say, “please don’t ever forget me”.

I turned my rear view mirror so I could keep my eyes on him the entire ride. Even all the way up through the handoff at the provider’s front door, he never closed his eyes and he never uttered a peep.

Most of our ride was in silence, except for when I spoke out loud to him in prayer.

“I’m so sorry for what you’ve had to endure so far in your short life on earth. You did not deserve any of it. I know that your life will continue to be difficult. Keep your faith. You are still here. You are strong. There’s so much good waiting for you. I love you so much and will always carry you with me in my heart.”

Some cases stay with you forever.

Wherever I go, I look out for Him.

“Each day I see Jesus Christ in all His distressing disguises.” — Mother Teresa

Children like this don’t just heal. Their wounds live deep beneath the surface, shaping the way they see the world and the way they move through it—impacting the way that we all do.

They get moved on to caregivers who are unskilled at recognizing and properly responding to high-needs children, often multiple times before adulthood.

Unresolved trauma begets further trauma.

Preverbal and Attachment Trauma: A Deep Dive into Early Developmental Wounds

Preverbal trauma and attachment trauma are distinct forms of early childhood trauma that occur before a child has the ability to verbalize experiences.

These traumas shape the nervous system, brain development, and core sense of self, often creating lifelong patterns in relationships, emotional regulation, and overall well-being.

Preverbal Trauma: The Silent Imprint

Preverbal trauma refers to traumatic experiences that occur before the development of language, typically in infancy and early toddlerhood (0-3 years old).

Because these experiences occur before explicit memory formation, they are not stored as conscious narratives but instead as implicit body memories, emotional imprints, and physiological states.

Causes of Preverbal Trauma

• Prenatal stress and trauma (e.g., maternal stress, domestic violence, substance use during pregnancy)

• Birth trauma (e.g., emergency C-sections, forceps delivery, umbilical cord issues, premature birth, NICU stays)

• Medical trauma (e.g., prolonged hospitalization, surgeries, lack of maternal presence during medical interventions)

• Neglect or deprivation (e.g., being left to cry for long periods, lack of attunement from caregivers)

• Early abuse (e.g., physical, sexual, or emotional abuse before the child can process experiences verbally)

• Adoption or foster care (e.g., being separated from the biological mother at birth)

• Sudden loss or absence of a primary caregiver (e.g., death of a parent, prolonged illness, postpartum depression)

How Preverbal Trauma Manifests Later in Life

• Unexplained anxiety and hypervigilance (often without a clear memory of “why”)

• Dissociation and emotional numbness (feeling disconnected from self and others)

• Chronic feelings of abandonment, rejection, or “not belonging”

• Attachment struggles (fear of intimacy, avoidant behaviors, or anxious clinging)

• Somatic symptoms (e.g., chronic pain, digestive issues, autoimmune conditions)

• Difficulty self-regulating emotions (e.g., sudden mood swings, extreme sensitivity to perceived rejection)

• Trust issues and difficulty forming secure relationships

• Reenactment patterns (e.g., unconsciously repeating past relational dynamics)

Because preverbal trauma is encoded in the body before language, traditional talk therapy often does not access these wounds directly.

Healing requires precision. Somatic (body-based) approaches—like trauma-informed bodywork, EMDR, somatic experiencing (SE), breathwork, and nervous system regulation—must be done by highly skilled practitioners.

Inexperienced trauma work can retraumatize rather than heal. In many cases, it leads to irreparable damage that doesn’t just stay with the individual—it echoes down through future generations.

Attachment Trauma: The Wound of Disconnection

Attachment trauma occurs when a child experiences chronic misattunement, neglect, or inconsistent caregiving in the first few years of life, leading to an insecure attachment style.

Types of Attachment Trauma

1. Avoidant Attachment Trauma (Dismissing)

• Develops when caregivers are emotionally unavailable, neglectful, or dismissive of the child’s needs.

• The child learns to suppress emotions and rely on self-sufficiency.

• Later in life: struggles with vulnerability, emotional intimacy, and trust.

2. Anxious Attachment Trauma (Preoccupied)

• Develops when caregivers are inconsistent—sometimes attentive, sometimes neglectful. Hugely prevalent today, as parents are more concerned with their digital and imaginary lives than their physical relationships and responsibilities.

• The child learns to cling to relationships, fearing abandonment.

• Later in life: experiences extreme anxiety in relationships, fears rejection, and may seek constant validation or disconnect completely.

3. Disorganized Attachment Trauma (Fearful-Avoidant)

• Develops when caregivers are both a source of comfort and a source of fear (e.g., abusive or unpredictable parenting).

• The child experiences a push-pull dynamic: craving closeness but fearing intimacy.

• Later in life: struggles with trust, may sabotage relationships, and often experiences emotional dysregulation.

4. Disoriented/Frightened Attachment

• Often found in children who experienced severe abuse, neglect, or abandonment.

• Leads to deep confusion, dissociation, and difficulty forming stable relationships.

• Later in life: may struggle with identity, dissociation, and self-destructive behaviors.

How Attachment Trauma Affects Adult Relationships

• Fear of abandonment or rejection (hypervigilance in relationships)

• Tendency to attract or be attracted to emotionally unavailable partners

• Fear of expressing needs or emotions due to early rejection

• Self-sabotage in intimacy (pulling away when things get too close)

• Codependency or extreme independence (“I don’t need anyone”)

• Chronic anxiety in relationships, needing reassurance but never feeling satisfied

• Emotional dysregulation in conflicts (overreacting or shutting down completely)

Attachment Trauma vs. Preverbal Trauma

While all preverbal trauma affects attachment, not all attachment trauma is preverbal. Some attachment wounds occur after language develops (e.g., childhood neglect, parental divorce at age 6), whereas preverbal trauma is stored outside of conscious memory.

Healing Preverbal and Attachment Trauma

Healing these deep-rooted wounds requires a multi-layered approach because traditional cognitive-based methods often do not access preverbal or attachment wounds effectively.

Key Healing Approaches

1. Somatic Therapy (Body-Based Healing)

• Trauma is stored in the nervous system, so healing must occur through the body, not just the mind.

• Methods: Somatic Experiencing (SE), EMDR, TRE (Tension & Trauma Release Exercises), Polyvagal Theory-based exercises, breathwork, neurofeedback.

2. Inner Child & Parts Work

• Reparenting wounded parts that still hold preverbal or attachment wounds.

• Methods: Internal Family Systems (IFS), guided imagery, compassionate self-inquiry.

3. Attachment Repair Therapy

• Creating new relational experiences that rewire the nervous system.

• Methods: Working with an attachment-informed therapist, secure relationship modeling, trauma-informed coaching.

4. Safe Relationships & Co-Regulation

• Healing happens in relationships, not isolation.

• Surrounding yourself with emotionally available, attuned people is crucial.

5. Spiritual & Energetic Healing

• Early trauma creates deep existential wounds around safety, belonging, and divine trust.

• Methods: Reiki, sound healing, meditation, breathwork, prayer, working with divine mother/father archetypes.

6. Releasing Implicit Memories

• Preverbal trauma cannot be accessed through logic or words alone.

• Methods: Body-focused therapies, movement, dance, expressive arts therapy, trauma-sensitive yoga.

Understanding And Patience Are Key For Successful Integration

Preverbal and attachment trauma are not personality flaws—they are survival adaptations formed before you had a choice. Understanding these wounds helps to compassionately decode your patterns and begin the process of deep healing. Because these traumas were formed in relationship, healing requires safe, attuned relationships that allow for new experiences of trust, connection, and safety.

This is as important for employers and community leaders to know, as it is for the wounded individuals.

If you start imagining that everyone you meet could have been a basketball baby too, perhaps you will start seeing the world with far more compassion.

I certainly hope that you do.